What is No Fault Divorce?

No-fault divorce is a legal process that allows couples to end their marriage without having to blame one another for the breakdown of the relationship. Unlike the old divorce grounds, such as committing adultery, no-fault divorce simply acknowledges that the marriage has irretrievably broken down without assigning fault to either party. This is now the only way to get divorced in England.

Under the no-fault system, one or both spouses can apply for a divorce by submitting an application confirming the marriage has broken down. This approach encourages a more amicable separation, as there is no requirement to provide evidence of (for example) someone’s poor behaviour.

What Are The Benefits of a No Fault Divorce?

The change in the law has brought benefits to couples, should a breakdown in marriage happen. These include:

- Reduces conflict: Married couples no longer have to put blame on the other to file for divorce, reducing further conflict throughout the process. Couples can now divorce on more amicable terms.

- Simplify the legal process: Since there is no evidence needed or no blame to investigate, the legal process is more straightforward. Focus and attention can be put into moving on from the divorce and rebuilding separate lives.

- Less Time Consuming & More Cost Effective: Reducing the legal process means the divorce will process quicker and reduce the costs.

- Prevents Contesting: With no one pointing blame, it prevents the spouse contesting the divorce, meaning, no one is forced to stay in an unhappy marriage.

- Fair Approach: With a more amicable divorce, it helps other agreements to be reached in a balanced approach, eg finances.

- Encourages Thoughtful Reflection: The 20-week mandatory reflection period ensures couples are making more rational decisions.

Conflict Reduction For Children: Having a more amicable divorce, it reduces the stress and strain on family life. It is easier for children when the parents can spend time navigating their co-parenting situation.

Before the law was reformed, divorcing couple needed to rely on one of five grounds in order to get divorced:

- Unreasonable behaviour

- Adultary

- Two years separation with the consent of the other spouse

- Five years seperation, in which case the other spouse’s consent was not needed

- Desertion.

It was a recipe for conflict because in order to secure an immediate divorce, one spouse had to accuse the other of either unreasonable behaviour or adultery. If they were not prepared to do that, they had to wait.

Owens v Owens

Whilst the pressure was mounting to change the way people obtained a divorce, the trigger for change proved to be the Supreme Court case of Owens v Owens [2018] UKSC 41.

The facts in the case of Owens v Owens are not dissimilar to many divorce cases, in that the wife, Mrs Owens filed a divorce petition in 2016 based on the only available ground for divorce which is that the marriage has irretrievably broken down. Mr Owens relied upon the most commonly used fact, which is that that her spouse had behaved in such a way that she cannot reasonably be expected to live with him’ and Mrs Owens gave particulars of incidents evidencing that fact.

What differentiated Owens v Owens from most divorce cases, was that in the large majority of cases, a divorce passes through court without any issue. In this case Mr Owens defended the petition on the basis that the particulars of behaviour relied upon by Mrs Owens were not sufficient to meet the test i.e.. that the marriage has irretrievably broken down. Whilst the Judge found that the marriage had broken down, he agreed with Mr Owens that the particulars of behaviour used did not meet the threshold and dismissed the petition.

The wife appealed the decision and the Court of Appeal returned to the question posed in the legislation which is, has the respondent behaved in such a way that the petitioner cannot reasonably be expected to live with the respondent? The Court of Appeal was satisfied that the first instance Judge had correctly applied the law and Mrs Owens’ appeal was dismissed.

The wife again appealed the decision in the Supreme Court in July 2018. Whilst they acknowledged the wife’s plight and that the decision troubled them, they recognised that their role was to interpret and apply the law laid down by Parliament. They therefore reluctantly dismissed the appeal and invited Parliament to reconsider the law on divorce. The impact on Mrs Owens of this was that she had little prospect of dissolving her marriage until five years had passed from the initial separation. This effectively prevented her from asking the Court to intervene to divide the substantial assets of the couple between herself and Mr Owens.

The decision in Owens v Owens demonstrated the need for Parliament to re-examine the current statute and inspire renewed pressure. That decision made clear to practitioners that until such a change that the law was amended, that petitioners would need to be encouraged to use more extreme examples of behaviour to ensure that they met the threshold to persuade the court that the marriage had irretrievably broken down. The impact of this was to either increase the animosity between the parties or force a party to remain in a marriage that they no longer wish to be in.

The Divorce, Dissolution and Separation Act 2020

Parliament eventually responded to the mounting pressure and a Bill was introduced on 12 June 2019. The Bill received Royal Assent on 25 June 2020 and the Divorce, Dissolution and Separation Act 2020 was passed. The Act was initially intended to be operative from Autumn 2021 but had been pushed back. It came into force on 6th April 2022. The new law applies to both divorce and the dissolution of civil partnerships.

The most significant change to the legislation is that the petitioning party will no longer need to establish fault. The new law allows one party, or a couple, to jointly petition for divorce, which will be achieved by making a statement of irretrievable breakdown, which will not require any explanation, and which cannot be contested.

The new legislation has disposed of the terms “decree nisi” and “decree absolute” and introduced plain English terminology which is fit for the modern age. The decree nisi will now be the “conditional divorce order” and the decree absolute the “final divorce order”.

No Fault Divorce Law Changes

- The requirement to meet one of the ‘five facts’ is removed, and the parties will only be required to produce a statement of irretrievable breakdown.

- It is no longer be possible for a spouse to contest the divorce, even if only one party believes that the marriage has irretrievably broken down.

- Either one party, or a couple, are able to jointly petition for divorce.

- The new legislation has disposed of the terms “decree nisi” and “decree absolute” and introduced plain English terminology which is fit for the modern age. The decree nisi will now be the “conditional divorce order” and the decree absolute will be the “final divorce order”.

- An extended minimum timeframe of 20 weeks has been introduced, which is intended to allow the divorcing couple to have a period to reflect on the decision to end the marriage.

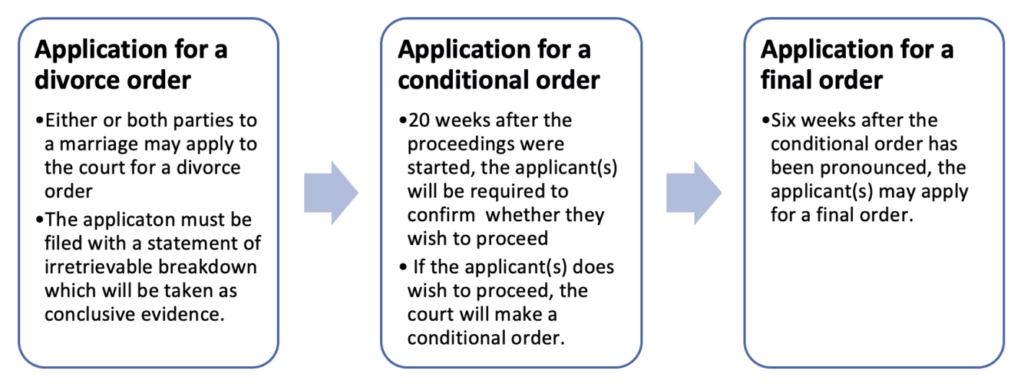

The procedure:

Conclusion

The introduction of The Divorce, Dissolution and Separation Act 2020 allows parties to have an amicable separation without the need of assigning blame. This encourages a non-confrontational approach, which will set the precedent for how parties approach other aspects of the separation, including any child arrangements and financial settlement. As such, it has been very widely welcomed by the profession.

At TV Edwards, we believe that this will make a real difference both to the harmful conflict that fault-based divorce encourages and to the cost to individuals of obtaining a divorce, as the new procedures will be much more accessible.

The changes will also bring to an end the small number of contested divorce proceedings, where one party either seeks to prevent the divorce from happening at all (as Mr Owens did), or tries to “cross petition”, effectively saying that the divorce should be granted to them, and for different reasons. Contested divorce proceedings are generally expensive and can increase the costs of obtaining a divorce from a few hundred to many thousands of pounds. For that reason, TV Edwards welcomed this development as a great improvement for our clients.

Divorce Help With TV Edwards

Here at TV Edwards, we have specialist divorce lawyers who are here to help you through all legal areas of the divorce process, including family finances, childcare agreements and more.

If you are considering applying for a divorce and want to discuss the right option for you, please contact our family team on family@tvedwards.com or 020 3440 8092.